Well boys and girls, we’ve done some things. If you’ve invested into The DAO, welcome to the largest crowdfunded/kickstarter/other “traditional analogy that doesn’t quite cut it” in history. The truth is, we’ve done something historical, and possibly game changing and foundational to how organizations pool and spend money (among other things). Let’s take some more time to look at who has invested, and how much has been put in, to see if we can draw some conclusions

In short: the more concise, truthful information that is put into more people’s hands results in more informed decisions. I speculate and draw my own conclusions, but the plots and numbers displayed herein are what they are — factual visualizations.

Of course, if you’ve got some sweet data chops yourself, all calculations and visualizations can be seen on my GitHub page. Take a look, let’s chat about it.

Basic assumptions

Because we don’t know all of the exchanges’ wallet addresses (at least I don’t, yet), we have to make a few assumptions of who they are based the number of transactions an address has and its total amount invested.

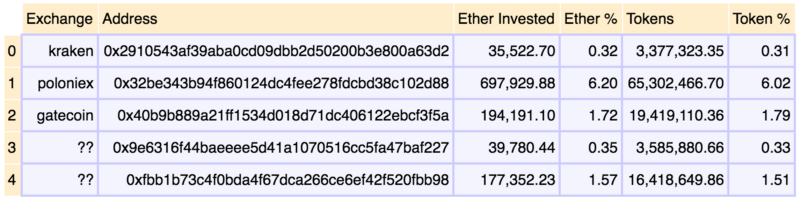

I have found tagged exchange addresses on EtherScan.io, cross referenced them against the DAO transactions, and they give the following information:

| Exchange | Ether invested | Number of transactions |

|---|---|---|

| Kraken | 35522.70303 | 275 |

| Gatecoin | 194191.10361 | 843 |

| Poloniex | 697929.88320 | 5826 |

Ok, so it’s clear that Poloniex has the majority of DAO purchases, and they’re all associated with one address (that I know of). But other exchanges that I found in the data run quite a range. Considering these numbers, I tagged any address that had over 30k Ether invested and over 100 transactions as an “exchange.” This led to the following table of “exchanges” :

Five addresses end up contributing around 10% of the total Ether invested into The DAO. That’s a lot! Let’s take a moment to ponder the implications.

What does this mean?

When purchasing DAO tokens on an exchange, one has to enter extra specific information into a “data field,” so that the exchange knows where to send the tokens.

The required data field means that the exchange doesn’t hold the tokens; it only sends the Ether from a user’s account (assuming the user didn’t screw it up), and the respective tokens that are generated go to the provided off-exchange address provided in the data field.

Essentially, all tokens associated with exchange purchases are distributed amongst addresses that I can’t see. Although we can’t know for sure yet, it is reasonable to assume that this group of addresses possesses the same wealth distribution as the addresses we can see.

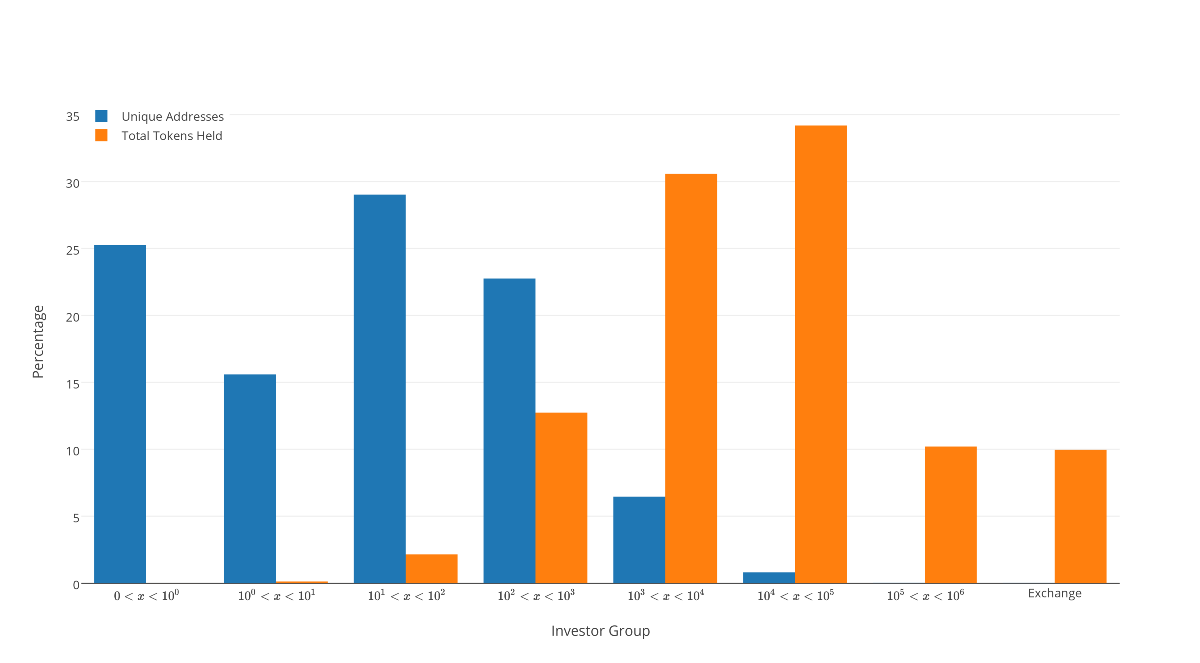

Namely, exchanges acting as platforms to purchase DAO tokens are not an issue, as they never control the tokens! During the creation phase, they’re only providing access points into the DAO, and are not acting as custodians of DAO tokens. Let’s take another look at wealth distribution, taking into account this new group, and see how it changes. Below is the same plot as the Part 1 blog post, but updated with the additional exchange group, and now we’re counting DAO tokens and not Ether because of the purchase rate changes.

Jeez, putting the exchanges in a separate category cut the last group of people in half. That means that 6 addresses, whoever they are, control ~10% of the voting power, instead of ~20%. While this does put more voting power into more people’s hands, the vast majority is skewed towards a relatively low percentage of addresses that own tokens: the very, very wealthy.

What could happen next?

If anything, this could lead to further token decentralization. There are many who have invested in The DAO because they plan on flipping the coins at a better rate than which they bought them. As more and more media attention flocks to this new and interesting concept, people will want in, and the tokens will be worth more simply due to demand.

This means people will buy tokens from others who have them, and at a premium, because no more tokens will be created. Good, somebody made a smart short-term investment decision and made some skrilla’. If you bought during the first phase of 100 DAO tokens for every Ether, then you can (more than likely) make a 50% return on your investment, considering people are still purchasing tokens at 100 DAO tokens for ever 1.5 Ether.

More importantly, every time someone who buys tokens from someone else, overall decentralization is increased, as the distribution of voting power of spread across more people. As more and more understanding and knowledge is spread about the DAO, investors with more informed opinions will buy tokens as well.

Furthermore, since its inception, many have jumped into throwing Ether at the DAO for FOMO (“fear of missing out,” for those of you who don’t know) purposes. Based on the severe lack of understanding of what The DAO is, how it operates, and what it wants to do, it isn’t a far cry to assume that many who’ve invested hope to make a quick buck, and a non-trivial percentage of those people are just going to split when they get their tokens to get their Ether back for a zero-sum gain.

Who these people are, and how it will effect the above chart, I don’t know. Also, I haven’t thought deeply enough to postulate an educated guess. Throw some comments at me — I’ll field them if they are sufficiently non-trollish.

When did people invest, and how much?

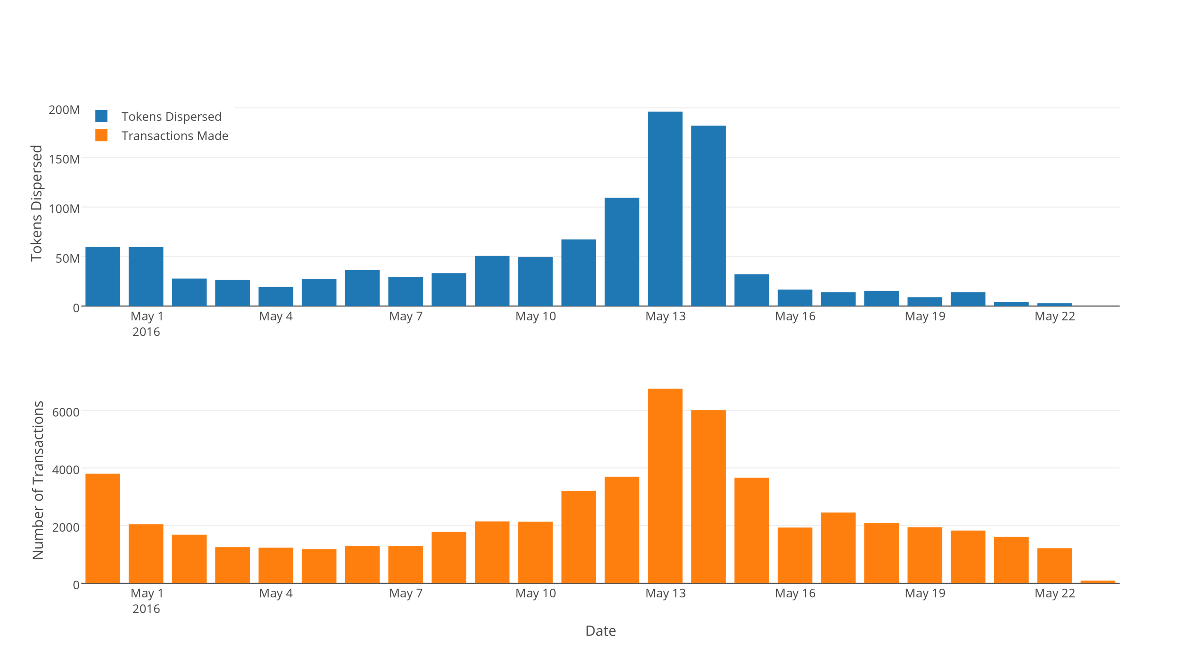

We’ve finished the rate changing days of the creation phase, so let’s check out the number of transactions/tokens distributed per day since this bad boy got started:

From the plot, high initial bars indicate that people were waiting to invest as soon as possible. This is followed by a steady flow of both transactions and received tokens, slowly growing until the tokens/ether rate started rising. We see a sharp increase and peak around the time of the rate change, and drastic decline in investments, due to the rate increase, and diminishing returns from Ether invested.

Put on your conclusions hat

This increase and peak is a product of many investors attempting to gather as much information as possible before throwing a large amount of money into something so very new, at the best rate they can. If this is true, we can at least know we have a high number of smart investors who care about their investments, gathered as much information as they could, and still decided to invest, which is ultimately good for the organization.

This also accounts for a large amount of the total Ether invested regardless of what group they lie in, meaning that the majority of tokens holders (more than likely) gather as much information as they can before making an investment decision.

Hopefully, this behavior translates to proposals. How we spend this money, and the subsequent change it generates, will ultimately tell whether or not The DAO is a success.