When reading about Bitcoin, Ethereum, Blockchain, other alt coins, etc… (I’ll use capital B — Blockchain here to encompass them all) I hear a lot of people say something akin to the following:

Blockchain can’t be good at everything, it has to choose one thing and be the best at it, and that should be <insert your idea here>.

Hell, I’m guilty of saying things like this myself, which is partly why I’m writing this. I am always weary of words like “can’t” and “never,” and when I find myself using them, I make a concerted effort to analyze why.

It turns out, people (as well as me) are saying these things with the presumption that they should behave like things they already understand. They are seeing Blockchain through the lens of traditional systems and how they behave, because those are the archetypes they have of the world. Our worldview is strictly defined by the tools we use to understand and explain it. This concept is certainly not new. In fact, the most popular variant was coined as “the law of the hammer” by Maslow in the mid 1900’s, which states:

If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail

The main idea of this is to warn from being narrow-minded. If you limit yourself to explaining the world with only the tools you’re comfortable with, you can quickly cut yourself off from a more complete description of what is going on. Even worse, you could completely get it wrong.

This becomes interesting if you take this idea, and apply it to how humans develop drastically new, innovative ideas. We, as a species, have spent an inordinate amount of time perfecting this pursuit. We call it science. It is notoriously difficult, slow, subtle, and cumbersome, but has lead to how we view the vast universe around us, and especially how we interact with it. The scientific method is the framework that pushes the boundary of human knowledge and understanding, but from the standpoint of Maslow, we are hammering the shit out of nature because the proper tool doesn’t yet exist to us.

In effect, we’re hammering the water in a pool and getting mad at the people next to us saying that isn’t going to work.

Thinking about genuinely new concepts is hard.

Unfortunately, because Blockchain and all its incarnations is an entirely new, completely innovative technology, we don’t have the experience, frame of reference, or developed tools to properly think about it. We are currently stuck using the tools of yesterday to describe a technology of tomorrow, because that is what is natural and easy to do. Unfortunately, the tools we have are incomplete because we’re describing something that transcends their scope of abilities.

I think the most elucidating way to highlight how our tools shape our perception is to discuss the history of mankind’s most innovative idea, Quantum Mechanics. I will not focus on details of quantum theory, it is beyond the scope of this post. This will instead be a broad, quick and dirty, overview of our conceptual evolution of nature, and how the tools of the trade played a role.

The Quantum Example: Is Light a Particle or a Wave?

Before Quantum Mechanics was discovered and developed, we had a different sets of rules that governed how the world around us operated, and they were well compartmentalized and satisfying. This was called Classical Mechanics, and people were pretty sure at the time that they got it right, except a few pesky areas that needed resolving (we’ll get back to these pesky areas later).

The world that Classical Mechanics described was governed mainly by two different sets of mathematical tools. The mathematics of describing particles, which is how you figure out where planets will be, where a cannon will shoot a cannonball, what happens when a car hits a brick wall, etc. Essentially, the energy of the system of interested was confined to a areas in space, and the math showed you how that energy moved about. The other was the mathematics of describing waves. This describes how ripples move through a liquid, how strings vibrate, and how sound travels through air. This set of mathematics describes the way energy can be spread across a medium continuously, and how it moves within that medium.

These two sets of mathematics did a great job explaining the world, for the vast majority of things we as humans tried to study. The universe was made up of waves and particles, and we developed an awesome toolbox of mathematics to describe both of those things, and all was good. The physicists of the time thought they were super smart, and figured out how to describe the world around them like the bad-asses they were. Only thing left was to just quickly figure out those little pesky areas that weren’t figured out yet, and then the description of the universe would be complete. Confidence was super high, the struts and arrogance were real.

One of those pesky areas was describing light. You know, that stuff the sun makes, and lightbulbs, etc? Was light fundamentally a wave or a particle? There became two competing camps that thought light was a particle or a wave. These scientists developed experiments to prove they were right. The wave scientists designed experiments to show how light behaved like a wave, using all the tricks of the trade they developed from wave mathematics. The particle scientists did the same. They used all the clever particle mathematics tricks to design experiments to prove that light behaved just like a particle. Herein lies the interesting part:

They all worked.

…

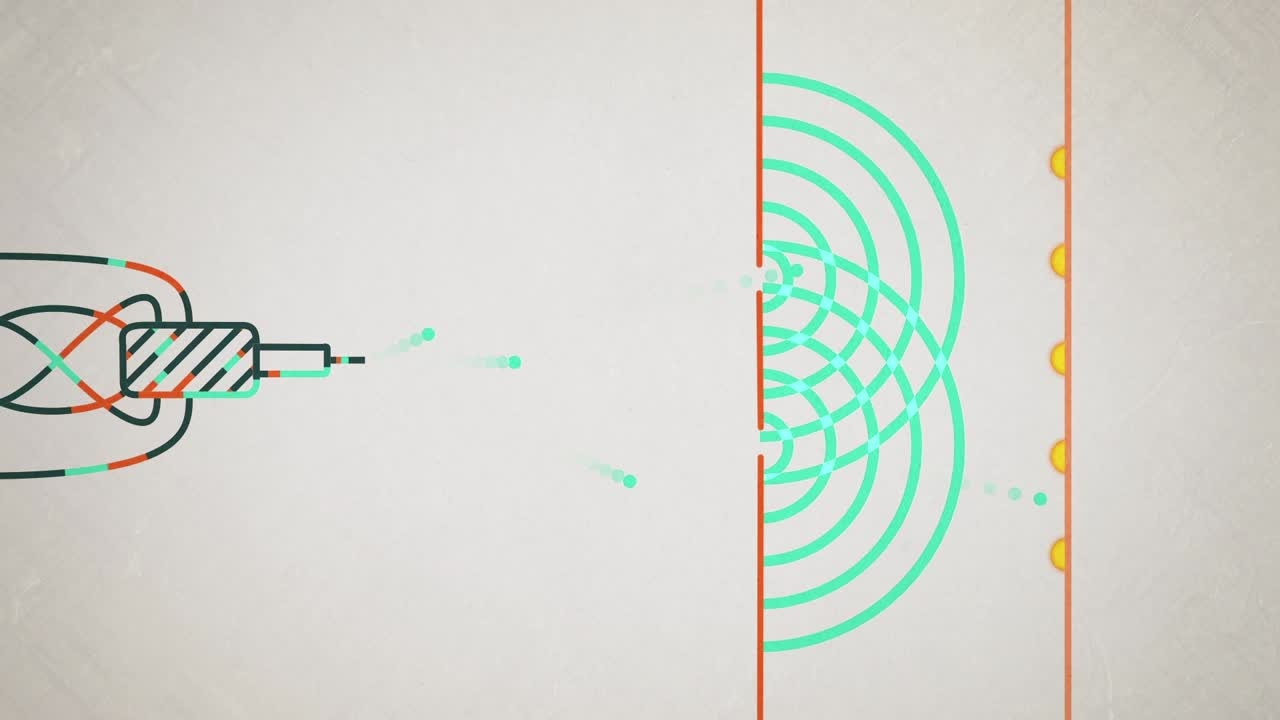

What? How can they both be right? How can light be both a wave and a particle at the same time? It turns out, light is neither and both at the same time, because it transcends the concepts of waves and particles, thus the tools and intuition that describes those things. The nature of light is more than a particle or a wave, so the tools scientists developed to describe waves and particles could never fully explain it. This is typically encapsulated in the canonical experiments and studies around “The Dual Slit Experiment” (google it).

This realization shook the foundation of our understanding of the world around us, and Quantum Mechanics was developed as a better mathematical model to explain the experimental phenomenon, and it worked REALLY well. But was difficult, and people were incredibly hostile towards it, because it shook the foundation of the ideology they created rooted in the old models. The universe was completely new and bizarre, and didn’t make sense. People didn’t like that, and they fought it tooth and nail, even Einstein.

Let’s Make Some Connections Now

When I see arguments and attacks on what Blockchain technology is for, it is incredibly reminiscent of the arguments of whether light was a wave or a particle. People clutch to their worldview and experience of a traditional system, which I call a “lens” in how they see the world around them, and use it to describe this new technology:

- “Blockchain is a store of value!”

- “No, it’s a medium of exchange!”

- “It was designed to be a central source of truth!”

- “It’s clearly best for immutable history, bro.”

- “Privacy guys, PRIVACY!”

Well… in my opinion, everyone is right and wrong at the exact same time. The invention of Bitcoin brought together multiple traditional technologies and married them together to create something ultimately more general than any of its components. We’re now experimenting with this brand new way of doing things to see how to make it better, and it’s called Blockchain.

Using any of the traditional toolsets to describe this new technology has value, but it is fundamentally incomplete.

Just like the mathematics of waves was incomplete (but useful) in describing the nature of light, the traditional tools people use for description and reasoning are incomplete (but useful) in describing Blockchain.

We’re currently spending more time arguing on who’s right using weapons of antiquity to defend ourselves. Instead, we should be looking for “The Quantum Mechanics of Blockchain,” A more complete description of a new transcendent technology, which is a generalization of all the tools used to describe the parts that make the whole. This will help transcend how we view the world around us, and usher a new beautiful means of human communication using computers.

I hope after reading this, you question the toolset you use to describe this space, and exactly how much you cling to it for comfort. Are you holding a hammer, getting mad at those telling you hitting the surface of a pool isn’t going to do anything useful? Are you a wave or particle scientist screaming at the opposite that your experiments work and that you’re right? What tools do you use to describe Blockchain, and what effect does that toolset have on your opinion of its purpose?

If that worldview is taken away, how scared are you?